Weathering

the Storm

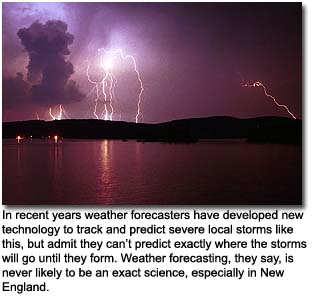

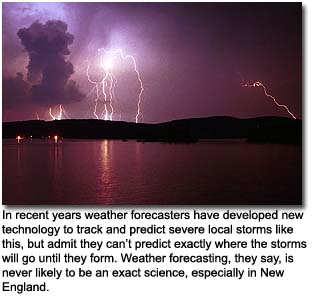

Boston weather forecasting is better than

ever, but forecasters say it will never be perfect

Images

and text are copyright © 2003 by Mike Colclough, all rights reserved.

Imagine

a job in which your words can virtually shut down the commerce of

a major metropolitan area. You can send its population of millions

into a panic, scrambling for food as if there's a famine. In the same

day, you might get blamed for a multi-car accident and a plane crash.

Imagine

a job in which your words can virtually shut down the commerce of

a major metropolitan area. You can send its population of millions

into a panic, scrambling for food as if there's a famine. In the same

day, you might get blamed for a multi-car accident and a plane crash.

It gets even more interesting. Complete strangers call you almost

every night for help planning their weddings. Their family barbeques.

Their vacations six months away. You name it, they expect your wise

words to help them plan. And you can't offer any. Most wouldn't understand

if you tried explaining. Every decision you make is based on the consensus

of a bunch of computers that are quite sophisticated, but often disagree

with each other when you need them most.

All through your daily routine, you're up against a society that's

addicted to your words and a news media that puts everything you say

underneath a huge magnifying glass. This is the job that Walter Drag

and his colleagues have wanted since they were children. Drag is a

meteorologist here in Boston, the weather capital of the nation.

***

It's

been a long and hard winter. The people are sick of snow, even the

snow lovers. Last spring brought snow on May 18. Then there was a

break with a bunch of hot days, until October 23 when it snowed again.

There was barely any time to rake up the leaves when snow covered

them in time for Thanksgiving. Another 12 inches fell on Christmas.

It kept snowing. Boston Harbor froze.

On a clear, calm March morning, the sun breaks above the blue horizon

of the Atlantic and casts a warm orange light on the east-facing walls

of nearly every house in the coastal town of Winthrop on the North

Shore. 52-year-old Drag is asleep in his home, alone. On the other

side of his bed are a Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society-his

field's largest professional association-and a recent issue of Weatherwise.

A jet thunders through the sky just a few feet over his rooftop, departing

Logan Airport a couple miles away. Drag was on a date the night before,

out dancing as usual, and stays asleep. The clock radio gets him at

6:30.

It's an oldies station, and the music's just ending when the DJ comes

on to read the forecast. It's supposed to go to 40 degrees, above

freezing for the first time in weeks. It's been in the forecast for

a few days, and Drag's one of the people who's been putting it there.

People across the area have been getting more excited about it all

week.

"People

want to know if there's going to be a thunderstorm during their family

barbeque in Natick at 1:30 pm on Saturday. How am I supposed to know

that? The [computer] models aren't that good yet, but I can't explain

that to the viewers."

- WBZ-TV 4 meteorologist Ed Carroll

Drag gets out of bed and showers, puts on blue jeans, black

socks, shoes, and tucks in a dress shirt but leaves the tie behind.

He's thin with dark hair, and youthful with a build that reflects

his interest in running charity races. He grabs his keys, heads out

and jumps into his compact 2002 Toyota for the 1-hour drive to Taunton,

where he works as a senior forecaster for the southern New England

headquarters for the National Weather Service (NWS).

He's passionate about work, and at first impression is outspoken,

vigorous, hyperactive. The word "indecision" doesn't seem

to be a part of his vocabulary. As a senior forecaster, he's also

required to work rotating shifts. For four or five days he'll work

overnights, from 11 pm to 9 am. After a couple days off, he'll come

in from 8 am to around 6 pm for a few days. The NWS schedules regular

staff meetings that occupy a lot of his days off. When at home, he

spends ten hours a week reading the professional journals and weather

magazines to keep up with the technology of his field. The commitment

cost him his two marriages. He doesn't have any children.

***

Drag's passion serves him well in a city where most people who tune

into the local news each night do so to see the weather. As a culture,

we're addicted to weather. And why shouldn't we be? New England has

the most rare climatology in the world. As if its weather weren't

complicated enough with the presence of nearby mountains, ocean, and

numerous river valleys, it's also the only region in the world where

more than two storm tracks merge. Storms and warm air come north along

the east coast. More storms come in from the west. Arctic air moves

south out of Canada. The ocean's influence frequently plays a role.

In 1991, all four factors became active at the same time. A cold air

mass moved out of Canada. Hurricane Grace came up from the south,

and a smaller continental storm moved off the coast. They combined

over the Canadian Maritimes to form a superstorm that began reversing

direction towards land. It hit on Halloween and became immortalized

as "The Perfect Storm" during conversations between Drag's

supervisor at the time and author Sebastian Junger.

All the unpredictability keeps the weather in the spotlight, and resulting

media hype is well known to Drag and his peers. Often their methodical,

scientific predictions mutate when they fall into the hands of drama-seeking

reporters. Small storms "grow" in the news before they ever

arrive in real life. It keeps people watching. It makes some people

panic. Meteorologists know our climate isn't that dangerous by comparison

to other parts of the country-although there can be tornadoes, Boston

area schools have no need to conduct tornado drills. Although there

have been hurricanes, our highways are not marked as "hurricane

evacuation routes."

As Drag sees it, the job is mundane and there's hardly ever a need

for panic. When the weather does provide for dangerous travel conditions,

he's responsible for getting the right warnings out in a timely manner.

Like most of his peers, he doesn't like to over-alert, or risk losing

credibility. Reporters, on the other hand, are trained to find good

stories, and a weather-related story in New England never has a hard

time getting an audience. Stations often compete for "best weather

coverage" and after a major storm, often run self-promoting advertising,

saying, "We gave you the best coverage of that storm." To

the scientific minds, it's purely hype. Drag considers it a trade-off:

Without the newscasts, there wouldn't be a means of getting the information

out at all.

***

Just after 8 am, Drag turns off of I-495 and enters the divided road

that takes him through the Myles Standish Industrial Park. The computer-aided

decisions he'll make in his day will become the background most of

the TV weathermen will look for when they arrive at their stations

later in the afternoon. Ahead of him is the radar dome, looking like

a giant ping-pong ball on 300-foot struts. It's the Weather Surveillance

Radar. Along with raindrops and snowflakes, it can show wind speed

and direction within a storm, and produce estimates of accumulated

rainfall.

Across the road from the radar ball is the brick building of the NWS.

For other forecasters in the area, the NWS is where their information

comes from. At Taunton, Drag and his colleagues work around the clock,

monitoring the weather and creating a number of products, all of which

end up at the TV and Radio stations.

Drag works in a big square room full of cubicles and semi-circular

workstations with four or five computers each. On one side of the

room there are two floor-to-ceiling magnetic maps of Southern New

England, one for river and lake levels, and another for keeping track

of weather warnings, which are issued by county. There's a digital

clock with global standard time (which is kept by pilots.) One workstation

has two radar screens. Suspended from the ceiling are monitors with

the radar picture and the Weather Channel.

Drag sits down at his workstation. Fresh in his mind is a 100-car

pileup that closed interstate 95 nearby a few days earlier. It happened

in a snowstorm he'd issued warnings for the day before it happened.

A foot fell across the South Shore and Cape Cod. The news reported

it as a "freak late season snowstorm" that struck without

warning, causing a major accident. No one was killed. After the accident,

the phone calls started coming in. First called the news reporters,

wanting to know if it had been predicted. Then the victims themselves

started calling, wondering why they hadn't heard about it before they

got in their cars that day.

"We predicted that one," he says. "We had a good handle

on it, we knew it was coming and we had the right warnings out the

night before. I don't know why some people are saying we didn't warn

them about it." His supervisor told him that a staff meeting

about it seems likely. He's prepared to defend himself and put it

behind him.

Drag's morning responsibility is to issue statements about flood potential

in southern New England. Though routine, the time of year raises their

importance. It's information that the public doesn't see, but TV meteorologists

monitor such statements and mention them when they need to.

On a computer monitor, Drag looks at the latest readings from river

gauges across the area. For a couple of hours he looks at all the

information that could foretell a flood. Snow depths. Water equivalent

of snow pack. Temperatures. Expected rainfall. He checks the numbers

in locations throughout the area. He's concerned about a spot of 40-inch

snow depths in the Connecticut River Valley near the Vermont-Massachusetts

line. His water equivalency map verifies that it's not just powder

snow fluffed up with air. It's the consistency of cement, chock-full

of water.

Meteorology

is one of the most complex sciences there is. What happens at ground

level is depicted on the "surface" maps forecasters show on

TV. Behind the scenes, they have maps of weather at levels between the

ground and the cruising altitude of your next international flight.

The slightest change in temperature, humidity, or wind direction over

one location can create a noticeable change in the future weather of

another.

"I hope it doesn't get too warm too fast or rain a lot,"

he says. "If that snowpack melted quickly we'd see a lot of problems.

That's an area we're going to have to watch as the weather starts

getting warmer." It's 11:30 am. Logan Airport is 45 degrees.

Finally Drag turns to hydrologist Ed Capone.

"It's looking pretty dry next few days, nothing significant in

the rivers this week, right?"

"Nope," replies Capone. "Too cold, not enough precipitation,

but soon though. Spring's coming!"

Using two fingers, Drag types out the "Daily river and lake summary."

A 2-inch statue of an Atlanta Braves player stands atop Drag's monitor.

"Yep, I'm a Braves fan," he says as he types.

His co-forecaster Jim Notchey sits at an adjacent workstation handling

the short term forecasting, marine and aviation weather.

"Then you've got some people who jump the bandwagon of whoever's

winning," says Notchey.

"Ok, that's usually me," says Drag, not missing a beat in

his typing.

The river statement is done and sent out. It's 12:30 pm and time for

lunch. He heads for the door.

***

Drag drives to a convenience store for some mini-pizzas to bring back.

He tells of the advances his field has made relative to medicine.

"Doctors have the technology to tell if someone's at risk for

cancer but they still can't tell with any certainty who's going to

get it and who's not. In weather forecasting we're making more localized

predictions and they're getting more accurate all the time."

For all its problems, media mutating of weather forecasts, and the

distrust of many people, the technology Drag uses is more advanced

than many would think. On TV many times a viewer will hear a forecaster

talk about "computer models" or "models." Scientists

like Drag use computerized models of the atmosphere to do most of

the predicting for them.

Computers are indispensable in making a forecast because meteorology

is one of the most complex sciences there is. What happens at ground

level is depicted on the "surface" maps forecasters show

on TV. Behind the scenes, they have maps of weather at levels between

the ground and the cruising altitude of your next international flight.The

slightest change in temperature, humidity, or wind direction over

one location can create a noticeable change in the future weather

of another.

Weather forecasting originated in the 1700's when Benjamin Franklin

noted that there were patterns to the weather's behavior and theorized

that weather could be tracked. Based on his theory, observation posts

were set up across the colonies, which ultimately became the NWS.

The math for weather forecasting existed around 1900 but couldn't

be done by many people. Computer-based forecasts first entered the

public spotlight when forecasters were put in charge of picking the

right day for the Allies to storm the beaches of Normandy. After the

war, the computers became available for civilian use. Until the 1970's

they weren't very sophisticated, but underwent major improvements

in the early 1980s and again within the last ten years.

Today's models are mainframe machines owned by the U.S. Department

of Commerce, Environment Canada, UK-Met (Great Britain's weather service),

and other European agencies. They're fed the present situation from

standardized weather stations and balloon launches across the country,

and worldwide. The computers recognize trends in the data, and spit

out predictions for every aspect of the weather at various altitudes

in locations everywhere.

Until the Internet became huge, this deluged forecasters with faxes

and paper maps of various altitudes they'd have to stack on clipboards

and shelves in their offices. They were always in black-and-white,

printed in dot matrix, and forecasters would have to take colored

markers to them before they could get an idea of what they were looking

at.

The newest thing in weather offices everywhere is the graphics displays.

They eliminate the need for the old paper analysis. Within the last

five years, the clipboards and shelves have been removed, and paper

maps are nowhere to be found. High-resolution monitors have replaced

them.

***

While

Drag is getting lunch, WBZ-TV 4 Meteorologist Ed Carroll is at home

with his wife and three young children, beginning to prepare his forecast

for the 6 pm newscast. He's the one that will ultimately present the

day's weather information to the wide audience. When he started at

WBZ ten years ago, he had to come into the station in order to look

at the maps generated by the computer models, and the statements issued

by the NWS staff. Today he logs on to his home computer to look at

the information he needs. The early look will allow him to be more

confident when he goes on the air in a few hours. Much more so than

Drag, Carroll has a critical audience that regularly lets him know

what it thinks, no matter what the opinion.

While

Drag is getting lunch, WBZ-TV 4 Meteorologist Ed Carroll is at home

with his wife and three young children, beginning to prepare his forecast

for the 6 pm newscast. He's the one that will ultimately present the

day's weather information to the wide audience. When he started at

WBZ ten years ago, he had to come into the station in order to look

at the maps generated by the computer models, and the statements issued

by the NWS staff. Today he logs on to his home computer to look at

the information he needs. The early look will allow him to be more

confident when he goes on the air in a few hours. Much more so than

Drag, Carroll has a critical audience that regularly lets him know

what it thinks, no matter what the opinion.

Carroll has to watch his wording. Since snow is still possible in

March, he might have to mention it in the forecast. On this 45-degree

day he's got an audience that's fed up with winter and suddenly thinks

it's spring. If he mentions snow, he'll get phone calls. If he doesn't

and it snows, he'll get even more phone calls. If the guy on the other

station is right more often than he is, Carroll could lose his job.

If the viewers decide they don't like him anymore, he could lose his

job anyway.

To make matters more complicated, Carroll works with the press. Mention

to them the possibility of a storm, and they jump on it. It becomes

news before it becomes reality. Sometimes it doesn't become reality.

Business is lost, flights get cancelled, the city turns upside-down

preparing itself for a false alarm, and the forecaster-not the reporter-is

the one who takes the heat. At home in winter, Carroll often checks

outside his window-more often than his kids do-to make sure it's snowing

when he said it would.

"It's the worst feeling in the world when you blow a forecast.

It's a really humbling experience that brings you back to reality,"

he says. "It forces you to check and see what went wrong."

He doesn't like alerting the news team to potential storms, though

he admits, "you have to."

"You tell them it's a four to eight inch event and they make

it out to be the storm of the century," he says. The conflicting

interests of reporters versus forecasters in a TV market led by weather

coverage has forced the two sides to meet regularly at the station

and reach agreements.

***

It's 1 pm, the time of day the major TV weather offices are empty.

The morning/noon personalities have gone home and the evening staff

isn't there yet. Back at his office, Drag slides over to a monitor

for the AWIPS (Automated Weather Information Processing System.) It's

got a map of the United States and he zooms in on various states,

showing airports by 3-letter codes, and by moving the cursor over

one he gets a pop-up with a complete weather observation there.

There's another monitor with a satellite connection for viewing any

kind of weather information he wants as soon as it becomes available:

satellite pictures, radar images, and output from the computer models.

It will color-code and display as many aspects of weather as he wants

at the same time, on local, regional, or national maps. With a click

of the mouse he sets it into motion-including model projections of

what will happen.

He logs on to a speakerphone system that allows him to join conferences

with forecasters at NWS offices nationwide. Today they're discussing

another late-season snowstorm over Wisconsin that's headed into northern

New England.

The office in Gray, Maine speaks up: "We think the situation

is good enough for heavy snow but not enough time. Maybe an elevation

event."

"Caribou, any comments?" asks a moderator.

"We agree with Gray, we just don't see a 7-inch event here."

"Burlington?"

"We're with Gray as well, the dynamics are there for heavy snow

but with the time constraint we see a 4 or 5-inch snow event with

isolated 7-inch amounts in the high terrain. How much can you get

in six hours?"

"Six inches!" shouts Drag at the machine, and turns it off.

He's not concerned about it because it's clearly tracking to the north.

Maybe only flurries for the Boston area. He's still got to mention

those, or else people will call in a panic because it's unexpectedly

snowing. Even if it's light and short-lived, the public will think

otherwise and will call for information about it.

The heads of commerce always call, pleading in vain for lighter storm

predictions. At the mention of a snowstorm, many people cancel every

appointment they have and hide. A false alarm can cost millions in

lost business throughout the area. On the other side of the coin,

a shy forecaster runs the risk of being asked to shovel eight inches

of "partly cloudy" off someone's driveway. Every so often,

the weather puts lives at risk. For that reason, the NWS's official

mission is to protect life first and commerce second.

Every time the computer models show a storm coming, it's up to the

forecaster to decide which model will be closest to reality. It's

like playing a mathematically-educated game of roulette.

"Wording is everything," says Drag. "As soon as you

mention 'thunder' in the summertime people want to know when and how

bad."

Drag says he was born in a thunderstorm.

"And you live in a fog!" shouts Notchey. They both laugh.

"I knew that was coming," he says. But he isn't kidding.

He was born in Manhattan in the middle of a thunderstorm, and wanted

to be a meteorologist as early as he can remember. His mom was a homemaker

who enjoyed redecorating, and his dad frequently away in the Merchant

Marines. They both wanted young Walter to be a doctor, but when they

realized they had a junior meteorologist on their hands, "they

were very supportive," he recalls. "They gave me a barometer,

thermometer, weather wheel that told you how to predict the weather

based on clouds and wind direction-they were great."

Growing up in New Jersey during the 1950s and 60s helped him become

the snow lover he is today. It was an era when the East Coast kept

getting buried in snow every winter.

"I loved sleigh riding. I really enjoyed my life as an elementary

school student."

His passion took him to St. Louis University "because I wasn't

good enough for Penn State," where he struggled through calculus

and physics problems.

He begins a long period of silence as he immerses himself in his work.

Despite all the government satellite feeds he gets, Drag uses the

internet to look at various graphical displays for the computer models.

One of his monitors has a college's meteorology web site up, and he

chooses from a huge table full of links to graphic presentations of

the models. To the untrained eye, the graphics look like colored spaghetti

on a plate shaped like New England.

At

the mention of a snowstorm, many people cancel every appointment they

have and hide. A false alarm can cost millions in lost business throughout

the area. On the other side of the coin, a shy forecaster runs the risk

of being asked to shovel eight inches of "partly cloudy" off

someone's driveway.

"Whoa! The UK-Met is onto it!" he shouts. For a few days

later, the British model shows a storm coming a lot closer to the

US east coast than it had earlier. It's a model that's been performing

pretty well in the previous few weeks. When any model gets on such

a "roll," it earns favor among forecasters until it starts

slacking.

None of the other models are saying anything about it. To predict

nothing at all runs the risk of having to "surprise" the

public with it later on. To announce it days early runs the risk of

giving the hype time to flame up and potentially ruin business.

He picks up the phone to NWS-Gray Maine.

"What do you think on this Thursday thing? The UK model's got

it trying to make a run up the coast at us."

There's a few seconds of silence on Drag's end. He starts clicking

links on his internet monitor in rapid-fire.

"Yeah, that's what I was thinking," he says, and hangs up.

He'd been predicting "snow showers" for the end of the week.

He changes it to "snow." This time he's taking the side

of not surprising the public.

Notchey's across the room working on a set of coastal marine forecasts,

and updating the aviation weather every hour. To be safe, Drag will

send his information over to Notchey's kiosk for cross-checking.

At 2:45 p.m., Drag starts typing out an "area forecast discussion."

It discusses all the thoughts he's having about what he's about to

forecast. Most of it's in meteorological shorthand, the way a physician's

notes are scribbled in a patient's file. It's where a forecaster will

state his confidence level and the likelihood that other situations

will occur. The discussion is one of the first bits of information

the TV guys will read when they get to work on the 6 pm report.

***

Drag

is still in the middle of his task when the phone rings. Notchey answers.

It's the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

"Ohhhhhh no! I don't want to hear this!" says Drag, cowering

behind his monitor.

"I don't want to hear this."

The room is silent while Notchey asks questions.

"How many were on board?" he asks. He writes on a piece

of scrap paper.

"Don't let me hear this," Drag repeats, softening his voice.

"I don't want to hear this."

"What type of aircraft was it?" asks Notchey, still writing.

"What's the tail number?"

Drag goes silent and tries to keep his focus on his work but his concern

is clear.

"And a description of the incident?" asks Notchey.

Any time there's an "incident" involving an aircraft within

an NWS office's area of responsibility, the FAA notifies that office

as a courtesy. If there's loss of life, Drag and Notchey-or whoever's

working at the time of the crash-have to fill out government reports

about the weather. The matter gets even more complicated if it's an

airliner, or any aircraft carrying a "VIP" or well-known

person. Drag's seen his share of those crashes. Because of the inexact

nature of the science, it's hard to prove a forecaster negligent in

the duty of issuing warnings, but that doesn't prevent the legal system

from putting him though a not-so-fun process of meetings and testimony

when weather-related death is involved.

Notchey hangs up.

"Well?" asks Drag.

"Single engine in Connecticut hit a snowbank while taxiing on

the ground. No injuries but I guess the plane didn't fare so well."

The mood lightens.

"I guess you could call that 'weather-related.' I mean if it

hadn't snowed last week the snowbank wouldn't have been there."

They both laugh. It's "pilot error" this time.

Drag gets his discussion out of the way and slides over to a fourth

monitor to run a "forecast editor." It allows him to make

maps of his forecast for all of southern New England, and sets them

to words for each city. Instantly, it becomes part of a national weather

database that can be accessed by anyone. When the evening shift comes

in, they'll start with his finalized work and continue improving it

through the night, as the computer models update their projections.

While making his forecast, he notes that the same model predicting

the snowstorm for the end of the week was hinting at the chance for

60-degree weather in two weeks' time.

"Sometimes these real extended deals are right. Often they're

not. They're not that good yet, that we can totally rely on them,

but it'll be fun to see if this actually pans out. I think a lot of

people could use a good dose of spring around here."

He hits a button his screen to "publish" his finished forecasts.

The computer gives Drag five or so minutes to kick back and take a

few gulps of coffee from his 1-liter Thermos, while the computer uploads

all his stuff to the system. Within an hour, the computer's words-representing

Walt Drag's graphics-will be read on radio stations around the Boston

area.

***

It's

3:30 pm. It's still sunny, temp 45 in Boston, and Walt Drag has just

called for more snow at the end of the week. It'll only be a matter

of hours before the public-perhaps even the weathermen-start calling

to complain. Bruce Schwoegler once told him "Everything you do,

I do opposite." Drag doesn't care anymore. His last half hour

of work will be briefing his night shift relief and passing the torch.

Over at Channel 4, Ed Carroll is in his office, surrounded by TV and

computer monitors. The smell of ozone mixes with the busy chatter

of newswriters following sattelite feeds on monitors, and on-camera

reporters preparing their scripts. Bob Lobel is in his office nearby,

reviewing a tape of the Red Sox in Spring Training.

Carroll, 40, is reviewing the forecast discussion Drag wrote. He's

seen the same models Drag's been looking at all day. His graphics

producer, also a meteorologist, already has TV-ready maps made for

him to stand in front of. It's sunny, yes. But they show snow at the

end of the week.

Carroll loves snow. He became interested in the weather after growing

up in Quincy and experiencing the Blizzard of '78. He loved the blowing,

the drifting snow, the thunder and lightning during the snow storm.

He went to Plymouth State College in New Hampshire to study meteorology,

and saw even more snow there. He was always happy about it.

Not today. Even Ed Carroll doesn't want to have to mention snow again.

From 5 pm until 6:30, he'll do weather updates every half hour (even

though the information they're based on comes from computer models

that only update every six hours.) After each update, maybe even during

the update, the viewers will call. No more snow, they'll say.

That's not all they'll say. A woman's already called a week earlier

to ask what the weather will be like for her vacation on foliage weekend

in October. She's only the first of the season. March is a "normal"

time for Carroll to start receiving those calls. And there are the

weddings. Requests for wedding day forecasts (almost always months

in advance) come every night.

As

Drag sees it, the job is mundane and there's hardly ever a need for

panic. When the weather does provide for dangerous travel conditions,

he's responsible for getting the right warnings out in a timely manner.

Like most of his peers, he doesn't like to over-alert, or risk losing

credibility. Reporters, on the other hand, are trained to find good

stories, and a weather-related story in New England never has a hard

time getting an audience.

"People don't know that we're not capable of predicting that

far in advance," says Carroll. "We're good, but we're not

that good." No one seems to know his limitations. Often Carroll

wishes he were the wizard many of his viewers think he is.

"It would sure make things a lot easier," he says. He laughs.

The slightest mention of "thunder" in a summer weather report

often yields calls from viewers who give their street addresses and

ask if there's a chance of localized rain on a specific date.

"People want to know if there's going to be a thunderstorm during

their family barbeque in Natick at 1:30 pm on Saturday. How am I supposed

to know that? The models aren't that good yet, but I can't explain

that to the viewers." They don't take his unknowing responses

very well. All he can do is be nice to them. They are, after all,

his viewers, the reason he has a job. Tonight, he's more worried if

the news crew will make a big deal out of his mentioning snow for

the end of the week. They're still doing follow-up stories on people

who were involved in the 100-car pileup in the last snowstorm, the

"freak, unexpected" one.

Carroll straightens his tie, puts on a suit jacket, and gets ready

for the camera. The day's work of Drag, coupled with Carroll's own

expertise, finally comes to the audience. Carroll knows they're happy

as they're tuning in. It's been sunny and 45 all day. For once, the

glaciers in their driveways began to melt. They want to know if it'll

stay that way. They're expecting a happy ending.

Carroll's not about to give it to them.

***

A hundred miles north of Boston at Plymouth State College where Carroll

attended, Jim Koermer is training tomorrow's meteorologists to use

the improved technology. At 55, he's been a meteorologist for 35 years

and received all his college-including a doctorate in meteorology-in

the U.S. Air Force. He began teaching weather at PSC in 1988.

On Monday mornings,13 students in the meteorology program file into

Koermer's classroom in the basement of the brand new Lamson Library.

Aware of Carroll and other successful alumni, they're excited for

their futures. Despite the dropouts due to the difficulty of the math,

the program's increasing its numbers steadily. At the beginning of

the school year, 90 first-year students came in as meteorology majors

and only 10 have since switched out.

The 13 in Koermer's classroom have been with him for three years.

It's the second semester of a year-long course in dynamic meteorology.

It's pretty much a math class based on differential equations. The

majors know it as "diffy-q," and to many of them it stands

for "difficult equations." Though the computers will do

all the math for them once they graduate, physics lessons teach them

how to spot differences between the models and real life weather.

"Models are sometimes fickle," says Koermer. "By knowing

physics you know when to believe them and when not to believe them.

A forecaster who always goes by the models is going to have some pretty

good busts along the way."

The meteorology Koermer's teaching is about the same as it ever was,

but the technology he's training his students to use is advancing

more rapidly than ever. A two-day forecast in 1980 had the same chances

of accuracy as a seven-day outlook does today. Many of Koermer's students

have accurately predicted weather ten days in advance.

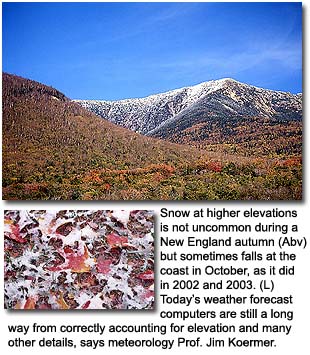

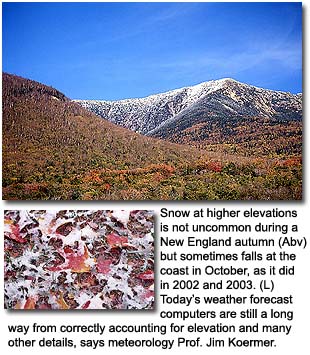

Koermer attributes improved accuracy to the optical resolution of

the models. In 1978, they "saw" the atmosphere in seven

altitudes with ground locations spaced at 381 kilometers. "That

barely accounted for topography like mountains," Koermer recalls.

"It made them flat." Since 1990, the model's vision of the

great blue yonder has improved to 60 altitudes and ground locations

10 kilometers apart. It's taking mountains into consideration, "but

it still reduces Mount Washington to half its height," says Koermer.

They're being programmed to consider tiny factors like moisture evaporating

from soil, but still have trouble with the amount of friction different

landscapes impose on the weather.

"Obviously a farm field is going to create less friction on a

weather system than mountainous or lots of big trees."

That difficulty is one reason Koermer feels weather forecasting will

never go beyond the two-week mark. Finally, he says, in order for

a computer model to be 100 percent accurate, scientists must first

program it with the "initial state of the atmosphere." That

would mean weather measurements from the beginning of Earth.

***

At

6:30 pm Walt Drag is almost back to Winthrop, and looking forward

to another night of dancing and dating. Over at Channel 4, Ed Carroll

has done his deed. As he walks back through the narrow, "backstage"

halls of WBZ, back to his office, his co-workers greet him: "Snow

again, Ed? Awww, come on!" From down the corridor he can hear

his phone ringing already. If it's not someone calling to complain,

it's someone who wants to know the weather for a July wedding date.

Perhaps it's another person wondering what Columbus Day weekend 2003

will be like in the mountains. Carroll fumbles through his pockets

for his car keys. Between the 6 and 11 pm newscasts he likes to drive

home and play with his kids.

The science of weather forecasting has come a long way since D-Day.

Computers will continue to evolve. College programs like Plymouth

State's are graduating better-trained forecasters than ever. Inevitably,

they and their computer models will still fail from time to time.

They're good, and they may become fabulous, but they won't be predicting

the weather for your wedding next summer.

Imagine

a job in which your words can virtually shut down the commerce of

a major metropolitan area. You can send its population of millions

into a panic, scrambling for food as if there's a famine. In the same

day, you might get blamed for a multi-car accident and a plane crash.

Imagine

a job in which your words can virtually shut down the commerce of

a major metropolitan area. You can send its population of millions

into a panic, scrambling for food as if there's a famine. In the same

day, you might get blamed for a multi-car accident and a plane crash. While

Drag is getting lunch, WBZ-TV 4 Meteorologist Ed Carroll is at home

with his wife and three young children, beginning to prepare his forecast

for the 6 pm newscast. He's the one that will ultimately present the

day's weather information to the wide audience. When he started at

WBZ ten years ago, he had to come into the station in order to look

at the maps generated by the computer models, and the statements issued

by the NWS staff. Today he logs on to his home computer to look at

the information he needs. The early look will allow him to be more

confident when he goes on the air in a few hours. Much more so than

Drag, Carroll has a critical audience that regularly lets him know

what it thinks, no matter what the opinion.

While

Drag is getting lunch, WBZ-TV 4 Meteorologist Ed Carroll is at home

with his wife and three young children, beginning to prepare his forecast

for the 6 pm newscast. He's the one that will ultimately present the

day's weather information to the wide audience. When he started at

WBZ ten years ago, he had to come into the station in order to look

at the maps generated by the computer models, and the statements issued

by the NWS staff. Today he logs on to his home computer to look at

the information he needs. The early look will allow him to be more

confident when he goes on the air in a few hours. Much more so than

Drag, Carroll has a critical audience that regularly lets him know

what it thinks, no matter what the opinion.